History of the Jews in Saudi Arabia

History of the Jews in Saudi Arabia

By the 6th and 7th centuries there was a considerable Jewish population in Hejaz (largely around Medina) and in Yemen due to the embrace of Judaism by the Himyarite Kingdom in the fourth century. Jewish leadership in Yemen ended soon after Dhu Nuwas instigated a massacre of the Christian community of Najran.[1][2]

According to Al-Masudi the northern part of Hejaz was a dependency of the Kingdom of Judah,[3] and according to Butrus al-Bustani the Jews in Hejaz established a sovereign state.[4] The German orientalist Ferdinand Wüstenfeld believed that the Jews established a state in northern Hejaz.[5]

Tribes of Medina

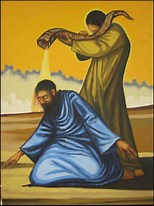

There were three main Jewish tribes in Medina before the rise of Islam in Arabia: the Banu Nadir, the Banu Qainuqa, and the Banu Qurayza. Banu Nadir was hostile to Muhammad's new religion. They joined the Mekkan army against the İslamic army and were defeated.Other Jewish tribes lived relatively peacefully under Muslim rule: Banu Nadir, the Banu Qainuqa, and the Banu Qurayza lived in northern Arabia, at the oasis of Yathrib until the 7th century. The men were executed and the women and children were enslaved after they betrayed the pact they made with the Muslims[6] following the Invasion of Banu Qurayza by Muslim armies led by Muhammad.[7][8]

Other tribes

- Banu Alfageer[9][10]

- Banu Awf

- Banu Harith or Bnei Chorath

- Banu Jusham

- Banu Quda'a

- Banu Shutayba

The journey of Benjamin of Tudela

A historical journey to visit far-flung Jewish communities was undertaken by Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela from 1165 to 1173 that crossed and tracked some of the areas that are located in present-day Saudi Arabia. One map of his travels shows that he stopped at Jewish communities living in Tayma and Khaybar two places that are known to have a longer significant historic Jewish presence in them, the Battle of Khaybar was fought between Muhammad and his followers against the centuries-long established Jewish community of Khaybar in 629. Tudela's trek began as a pilgrimage to the Holy Land.[12] He may have hoped to settle there, but there is controversy about the reasons for his travels. It has been suggested he may have had a commercial motive as well as a religious one. On the other hand, he may have intended to catalogue the Jewish communities on the route to the Holy Land so as to provide a guide to where hospitality may have been found for Jews travelling to the Holy Land.[13] He took the "long road" stopping frequently, meeting people, visiting places, describing occupations and giving a demographic count of Jews in every town and country.

One of the known towns that Benjamin of Tudela reported as having a Jewish community was "El Katif"[14] located in the area of the modern-day city of Hofuf in the northern part of the Arabian Peninsula. Al-Hofuf also Hofuf or Al-Hufuf (Arabic: الهفوف) is the major urban center in the huge al-Ahsa Oasis in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. The city has a population of 287,841 (2004 census) and is part of a larger populated oasis area of towns and villages of around 600,000. It is located inland, southwest of Abqaiq and the Dhahran-Dammam-Al-Khobar metropolitan area on the road south to Haradh.

Najran community

There was a small Jewish community, mostly members of Bnei Chorath, in one border city from 1934 until 1950. The city of Najran was liberated by Saudi forces in 1934 after it been conquered by Yemenis in 1933, thus absorbing its Jewish community, which dates to pre-Islamic times.[15] With increased persecution, the Jews of Najran made plans to evacuate. The local governor at the time, Amir Turki ben Mahdi, allowed the 600 Najrani Jews[16] a single day on which to either evacuate or never leave again. Saudi soldiers accompanied them to the Yemeni border. These Jews arrived in Saada,[17] and some 200 continued south to Aden between September and October 1949. The Saudi King Abdulaziz demanded their return, but the Yemeni king, Ahmad bin Yahya refused, because these refugees were Yemenite Jews. After settling in the Hashid Camp (also called Mahane Geula) they were airlifted to Israel as part of the larger Operation Magic Carpet.[18]

Some groups of Najran Jews escaped to Cochin, as they had very good relationship with the rulers of Cochin and maintained trade connections with Paradesi Jews.[19]

According to Yemenite Jewish tradition, the Jews of Najran traced their origin to the Ten Tribes.

Modern era

There has been virtually no Jewish activity in Saudi Arabia since the beginning of the 21st century. Jewish (as well as Christian and other non-Muslim) religious services are prohibited from being held in Saudi Arabia.[20] When American military personnel were stationed in Saudi Arabia during the Gulf War, permission for small Christian worship services was eventually granted, but Jewish services were only permitted on US warships.[20] Census data does not identify any Jews as residing within Saudi Arabian territory.[21]

Historically, persons with an Israeli stamp in their passport or who are openly religious (and not Islamic) were generally not permitted to enter the Kingdom. In the 1970s, foreigners wishing to work in the kingdom had to sign an affidavit stating that they were not Jewish[22] and official government forms granting foreigners permission to enter or exit the country do ask for religious affiliation.

During the Gulf War, there were allegations that some United States military authorities were encouraging Jewish military personnel to avoid listing their religions on their ID tags.[23] (It has been reported that Jewish personnel, along with others, were encouraged to "use discretion" when practicing their religion while deployed to Saudi Arabia).[24] American servicemen and women who were Jewish were allowed into the kingdom, but religious services had to be held discreetly on base. It has been affirmed that alternative "Protestant B" dog tags were created, in the event that a Jewish serviceman or woman was taken prisoner in Iraq.[25] The story was included in one civilian writer's anthology of military stories she had been told by others, and then that one story was reprinted or quoted in many other in-print or online locations including Hadassah Magazine). It has been the subject of much debate as to its veracity, with some military personnel stating that the story is "absolutely false."[24][26]

In late December 2014, the newspaper Al-Watan reported that the Saudi Labor ministry website permits foreign workers of a variety of different faiths, including Judaism, to live and work in Saudi Arabia. A source within the ministry said, in effect, that Israelis were not allowed to enter Saudi Arabia, but Jews of other nationalities would not have the entry ban applied to them.[27] In practice Christians and Jews may hold religious services but only in their homes and may not invite Muslims. However, as of May 2022, Israeli media outlets reported that dozens of Israelis were able to enter Saudi Arabia with Israeli passports using special visas.[28][29] According to some Jewish expatriates living in the Kingdom, there are around 3,000 Jews who currently reside in Saudi Arabia, mostly from the US, Canada, France, and South Africa.[30]

Since 2019, Rabbi Jacob Herzog, an American-born Israeli agribusiness entrepreneur, has been visiting Saudi Arabia[31] to establish connections with its Muslim religious leaders, and visiting Jewish tourists, business representatives, and American military personnel, with the goal of organizing a Jewish community.[32]

After the Abraham Accords, Saudi Arabia outlawed the disparagement of Jews and Christians in mosques, and also removed anti-semitic passages from school textbooks.[33]

On 3 October 2023, Israeli Communications Minister Shlomo Karhi participated in a Jewish morning prayer service in Riyadh on the Sukkot holiday that included a Torah scroll dedicated to "King Salman bin Abdulaziz, Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman and all their ministers and advisers." Karhi's visit was part of an effort by Israel and Saudi Arabia to normalize their diplomatic relations.[34]

Judaism in pre-Islamic Arabia

When does anti-Zionism become antisemitism? A Jewish historian’s perspective

When does anti-Zionism become antisemitism? A Jewish historian’s perspective

In his latest book, Jewish Life in Medieval Spain, Jonathan Ray focuses on the tumult of the 14th century in Spain – a time of the plague, civil strife and war between the two largest kingdoms, Aragon and Castile, with frequent attacks against Jews. This culminated in riots in 1391, which resulted in deaths, destruction of property, rapes and forced conversions.

Ray describes an appeal the Jewish community made to the Spanish king in 1354, describing the hatred they faced:

[…]the people made the earth tremble with their cries of: “all this is happening because of the sins of Jacob [later renamed Israel]. Let us destroy this nation! Let us kill them!”

Treating Jews as scapegoats during times of hardship is an ongoing feature of Jewish history. Some 100,000 Jews were murdered in eastern Europe as part of the struggles following the 1917 Russian Revolution. These attacks were followed by the tragedy of the Holocaust.

Jews were also targeted in riots in the Middle East and North Africa during the second world war. During the Farhud of 1941, for example, a violent mob attacked the Jews of Baghdad, killing up to 180 people, raping women and looting properties.

An awareness of this ongoing history of persecution is important to understand the trauma of the October 7 attack by Hamas in southern Israel, during which 1,200 people were killed (and some sexually assaulted) and around 240 people abducted. It was a watershed moment for Israelis, as well as the Jewish diaspora.

It also helps to understand the Jewish perspective on some of the rhetoric heard at global protests against Israel’s subsequent war in Gaza – and more broadly against Zionism – since October 7. To many, this equates to antisemitism.

When anti-Zionism leads to antisemitism

Much ink has been spilt on the issue of whether protests against Zionism, or anti-Zionism, are inherently antisemitic.

Certainly, within the academic realm, anti-Zionism does not necessarily conflate with antisemitism. As Michelle Goldberg recently wrote, anti-Zionism can emerge from those who believe in the potential for Israelis and Palestinians to live together in the same state, or from well-intentioned concerns for Palestinian suffering, among other reasons.

However, when the real-life impact of anti-Zionism results in cries advocating for the killing of Jews, then it can only be understood as antisemitism. As is any criticism of Zionism or Israel that crosses the line into blatant racism or discrimination, demands to de-platform or exclude Zionists, the resurfacing of tropes and conspiracy theories about Jewish people, or the questioning of Israel’s right to exist as a state.

On October 9, just two days after Israel’s declaration of war against Hamas, a pro-Palestinian rally took place in Sydney with clear parallels to 1354.

While the police may quibble as to whether the protesters’ chants were “gas the Jews” or “where’s the Jews”, for Jewish people, the intent was the same.

The crowd at another rally at the Victoria parliament chanted “Khaybar, Khaybar, the armies of Muhammed are coming”. This refers to attacks by the Muslim army against the Jewish tribe in Arabia in 628, when Jews were subjugated, expelled or slaughtered.

These hateful messages coincided with an unprecedented upsurge of antisemitism in Australia – an increase of 738% since October 7, according to the Executive Council of Australian Jewry. These acts included vile graffiti messages, the boycotting of Jewish businesses deemed “Zionist”, verbal abuse (including death threats), physical abuse and attacks on social media.

This rising antisemitism – as well as the lack of empathy and support many Jewish people felt in Australia following the October 7 attack – is what led to the formation of the Jewish creatives and academics WhatsApp group.

Its members were later shocked at the leaking of their chat with personal details and photos, as well as the threats and abuse some experienced. As Jewish historian David Slucki stressed, such doxxing has no justification.

Some have argued the release of the chat messages was whistleblowing because the group was trying to suppress pro-Palestinian voices. To Jewish members, however, this argument evokes ancient tropes of secret Jewish cabals. It also suggests that being Zionist automatically means one is anti-Palestinian. Such assumptions foster antisemitism, the clear outcome of the leak.

For example, the ongoing idea of Jews having “tentacles” that reach far and wide to control people was recently resurrected by Jenny Leong, a Greens MP for Newtown (who later apologised).

Where Zionism comes from and how it’s evolved

To understand what anti-Zionism is, one needs first to understand what Zionism means.

The word “Zion” stems from the bible. It refers to a mountain in Jerusalem where King David, one of the most revered figures in Jewish history who conquered Jerusalem in the 10th century BC, is believed to be buried.

Over millennia, “Zion” has come to refer to Jerusalem itself, as well as the Land of Israel. Zionism is also the Jewish national self-determination movement, which emerged in the 19th century to create a Jewish state in the Jews’ ancestral homeland, Israel. This goal was achieved in 1948.

Before 1948, there were Jews who opposed the Zionist movement for different reasons. The ultra-Orthodox believed Jews had to wait for the coming of the Messiah and creation of a theocratic state. Secular socialists, meanwhile, believed Jews needed to fight for full equality and self-determination in their own countries.

As he discusses in his autobiography, Jewish journalist Michael Gawenda grew up with such an anti-Zionist viewpoint, but gradually shifted his views on Israel. Then, he says, the world changed on October 7. As he suggests in a recent article, some of those criticising Israel on the left today see the state as “the bastard child of an evil ideology”. He writes:

The Hamas pogrom and its aftermath — the explosion of antisemitism and Jew hatred [around the world] — reminded Jews like me that in Jewish history, what may have seemed to be a golden age for Jews can end suddenly, violently, inexplicably and with devastating and sometimes murderous consequences.

In a recent survey, 77% of Australian Jewry identified as Zionist and 86% agreed the existence of Israel was essential for the future of the Jewish people.

Many anti-Zionists today, particularly among the progressive left, however, believe Israel was “born in sin” as a racist, settler-colonial state. In their view, Zionists are pursuing ethnic cleansing, expulsions, theft, apartheid and genocide against the Palestinians.

These beliefs were also propagated by the Soviets from the early 1960s as part of their efforts to win over the Arab world.

It is important to stress that criticising the Israeli government’s actions towards the Palestinians is not inherently anti-Zionist. This includes legitimate criticism of Israel’s conduct of the war in Gaza and the government’s failure to set out clear plans for the aftermath of the war.

For example, US Senator Chuck Schumer, who is Jewish, recently strongly criticised the actions of Benjamin Netanyahu’s government. Schumer is one of the most pro-Israel senators in US history. He cannot be considered an anti-Zionist.

Conflicting definitions on antisemitism

In recent years, efforts have been made to define antisemitism to show how it intersects with attitudes towards Israel and to draw clearer lines explaining when anti-Zionism becomes antisemitism.

This culminated in the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s adoption of a working definition of antisemitism in 2016. While stressing that legitimate criticism of Israel is not antisemitism, seven of its 11 examples of antisemitic behaviour relate to Israel. These include:

-

denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, for example, by claiming the existence of a state of Israel is a racist endeavour

-

drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis

-

holding Jews collectively responsible for actions of the state of Israel.

To date, 38 nations have accepted this definition of antisemitism, including Australia in 2021.

Some scholars, including those who would consider themselves anti-Zionists, however, have rejected the definition and developed and signed another, known as the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism.

A small minority of Jews who oppose Israel’s existence as a Zionist state adhere to this definition. For other Jews it is seen as more accurate because it is less prescriptive than the IHRA definition and also seeks to “clarify when criticism of (or hostility to) Israel or Zionism crosses the line into antisemitism and when it does not”.

For instance, it says criticising or opposing Zionism “as a form of nationalism” is not antisemitic, while “denying the right of Jews in the state of Israel to exist and flourish” would be.

As Jewish historian Derek Penslar explains in terms of why he signed it:

There are a great many people in the world who bear no animus against Jews but who are troubled by Israel’s treatment of Palestinians and want it to change. Such critics include Jews who are deeply attached to Zionism as an ideal and Israel as the fulfilment of that ideal.

Without an historical lens, it’s not possible to fully understand the complex interconnections between anti-Zionism and antisemitism today.

Instead of the polarising pro-Palestinian and anti-Zionist narratives we are currently seeing, our aim should be to work towards understanding each other’s pain and learning to listen to each other with respect, even if we choose to agree to disagree. We seem to have a long way to go to achieve this goal.

- Jonathan Este :Senior International Affairs Editor, Associate Editor: Published: March 27, 2024 11.15pm GMT

Vatican banishes archbishop who branded Pope Francis 'servant of Satan'

Vatican banishes archbishop who branded Pope Francis 'servant of Satan'

Carlo Maria Vigano has built a following of his own since delving into coronavirus conspiracy theories and criticising the Catholic Church's efforts to modernise.

Carlo Maria Vigano remained unrepentant after the Vatican's decision. File pic: Reuters

An ultra-conservative archbishop has been excommunicated by the Vatican after being found guilty of schism.

Schism is one of the gravest crimes in canon law and occurs when someone withdraws submission to the Pope or his Catholic subjects.

Carlo Maria Vigano served as the Vatican's ambassador to the US from 2011 to 2016 but went into hiding in 2018.

This came after he alleged Pope Francis knew about US cardinal Theodore McCarrick's sexual misconduct and did nothing about it.

The Vatican has rejected this claim.

Vigano also branded the Pope a "false prophet" and a "servant of Satan", before calling for him to resign.

The Vatican's doctrinal office announced the 83-year-old's excommunication - or banishment - on Friday.

It said his previous comments made it clear he refused "to recognise and submit" to the head of the Roman Catholic Church.

Vigano had also rejected the legitimacy of liberal reforms made by the church in the 1960s, it added.

The statement read: "At the conclusion of the penal process, the Most Reverend Carlo Maria Vigano was found guilty of the reserved delict (violation of the law) of schism."

The excommunication means Vigano is formally outside the church and cannot celebrate or receive its sacraments, such as communion.

As is normal, the ruling was signed by the head of the Doctrine of the Faith office instead of the Pope himself, but it's highly unlikely the punishment was given without his approval.

Responding on X, where he has frequently posted while in hiding, Vigano remained unrepentant and urged Catholics to support him with a quote from Jesus in the New Testament: "If they keep quiet, the stones themselves will start shouting."

Vigano has cultivated a following of like-minded ultra-conservatives over the years, delving into conspiracy theories and labelling the coronavirus pandemic the "Great Reset".

In a post on X last month, he criticised the Vatican's proceedings against him and accused Pope Francis of representing an "inclusive, immigrationist, eco-sustainable, and gay-friendly" church.

- Reference: Sky News:

Vatican ‘deplores the offence’ caused by Last Supper skit in Paris Olympics ceremony

Vatican ‘deplores the offence’ caused by Last Supper skit in Paris Olympics ceremony

The Vatican said it was “saddened by certain scenes” at the Paris Olympics opening ceremony which at one point appeared to parody the Last Supper with scantily dressed performers.

The scene performed on July 26 has angered Christian organisations for its apparent recreation of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper with drag queens and a naked singer.

Although organisers defended the skit as a portrayal of a pagan feast led by Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, many remain unconvinced.

“The Holy See was saddened by certain scenes at the opening ceremony of the Paris Olympic Games and can only join the voices that have been raised in recent days to deplore the offence caused to many Christians and believers of other religions,” the Vatican said in a statement, originally in French.

“At a prestigious event where the whole world comes together to share common values, there should be no allusions ridiculing the religious convictions of many people. Freedom of expression, which of course is not in question, finds its limit in respect for others.”

Dancers and drag queens

The tableau, titled Festivity, began with a group of dancers and drag queens sitting around a long table. It was part of a section celebrating the French capital’s vibrant night life and reputation as a place of tolerance, pleasure and subversiveness.

Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia, head of the Vatican’s Pontifical Academy for Life, said the importance of the Olympics and its sporting values had been besmirched by “a blasphemous mockery of one of Christianity’s holiest moments”.Avvenire, an Italian newspaper affiliated with the Church, criticised the show in a lengthy editorial, saying: “What is the sense in transforming every event on the planet (even sporting) into a ‘gay pride’?”.

Matteo Salvini, Italy’s deputy prime minister and far-Right leader, described it as an insult to billions of Christians around the world while Tommaso Foti, the head of the Brothers of Italy in the lower house, condemned it as “blasphemy”.

The Last Supper is a mural painted by Leonardo da Vinci in the late 15th century in the Santa Maria delle Grazie convent in Milan. It depicts Jesus with the 12 apostles, showing the moment after he announced that one of them will betray him.

The organisers of the Paris Olympics last week apologised for any offence the scene caused. Anne Deschamps, a spokesman, said: “Clearly there was never an intention to show disrespect to any religious group.” The opening ceremony “tried to celebrate community tolerance”, she added.

- Story by Josephine McKenna: The Telegraph

Articles-Latest

- Koran burning conviction sparks fury as blasphemy law 'returns to UK'

- Robert Francis Prevost - Pope Leo XIV

- Pope Francis' death follows recent health challenges. Here's what we know about how he died.

- Easter April 2025 - international Celebrations

- The Rule of the twelve psalms -Worthy is the Lamb

- Religion in Africa Before Christianity and Islam

- 6 The Origin of Yahweh

- Dumo Di Milano

- What Did the Crow Tribe Believe In: Discover The Beliefs!

- 7 Reasons Historic Christianity Rejects the Book of Enoch

- 8 Breathtaking Mountain Monasteries Around the World

- Ethiopian Bible is oldest and most complete on earth

- Muhammad Muhammad was a prophet and founder of Islam.

- World Day of the Poor – SVP Christmas Campaign 2024

- Pope Francis to open 5 sacred portals on Christmas Eve — for a ritual that’s never been done before

- The 144,000 in Revelation

- Over 73 dead bodies 'used for meditation', 600 crocs in a pond, found in two Thai temples

- Occultism: Western Occult Tradition

- What is a Mudra

- Blood Sacrifices: Ancient Rituals of Life and Death

Articles-Most Read

- Home

- Let There Be Light

- Plants that feel and Speak

- The Singing Forest

- The Singing Forest-2

- Introduction

- Meditation

- Using Essential Oils for Spiritual Connection

- Heaven Scent

- Plants that Feel and Speak-2

- Purification

- Making the Spiritual Connection

- Anointing

- Essential Oils: The unseen Energies

- The Sanctity of Plants

- The Aroma Of Worship - Introduction

- The Aroma Of Worship-Foreward

- Methods Of Use

- Spiritual Blending

- Handling and Storage