Fatima

Fatima

This article is about Muhammad's daughter. For other people named Fatima, see Fatima (given name). For the town in Portugal, see Fátima, Portugal. For the Marian apparition, see Our Lady of Fátima. For other uses, see Fatima (disambiguation).

Fatima bint Muhammad (Arabic: فَاطِمَة بِنْت مُحَمَّد, romanized: Fāṭima bint Muḥammad; 605/15–632 CE), commonly known as Fatima al-Zahra' (Arabic: فَاطِمَة ٱلزَّهْرَاء, romanized: Fāṭima al-Zahrāʾ), was the daughter of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and his wife Khadija.[1] Fatima's husband was Ali, the fourth of the Rashidun Caliphs and the first Shia Imam. Fatima's sons were Hasan and Husayn, the second and third Shia Imams, respectively.[2][3] Fatima has been compared to Mary, mother of Jesus, especially in Shia Islam.[4][5] Muhammad is said to have regarded her as the best of women[6][7] and the dearest person to him.[8][6] She is often viewed as an ultimate archetype for Muslim women and an example of compassion, generosity, and enduring suffering.[4] It is through Fatima that Muhammad's family line has survived to this date.[9][7] Her name and her epithets remain popular choices for Muslim girls.[10][11]

When Muhammad died in 632, Fatima and her husband Ali refused to acknowledge the authority of the first caliph, Abu Bakr. The couple and their supporters held that Ali was the rightful successor of Muhammad,[4] possibly referring to his announcement at the Ghadir Khumm.[12] Controversy surrounds Fatima's death within six months of Muhammad's.[13] Sunni Islam holds that Fatima died from grief.[3] In Shia Islam, however, Fatima's (miscarriage and) death are said to have been the direct result of her injuries during a raid on her house to subdue Ali, ordered by Abu Bakr.[14] It is believed that Fatima's dying wish was that the caliph should not attend her funeral.[15][16] She was buried secretly at night and her exact burial place remains uncertain.[17][18]

Name and titles

Her most common epithet is al-Zahra (lit. 'the one that shines, the radiant'),[6] which encodes her piety and regularity in prayer.[19] This epithet is believed by the Shia to be a reference to her primordial creation from light that continues to radiate throughout the creation.[6] The Shia Ibn Babawahy (d. 991) writes that, whenever Fatima prayed, her light shone for the inhabitants of the heavens as starlight shines for the inhabitants of the earth.[20] Other titles of her in Shia are al-Ṣiddiqa (lit. 'the righteous'),[11] al-Tahira (lit. 'the pure'),[21] al-Mubaraka (lit. 'the blessed'),[21] and al-Mansura (lit. 'helped by God').[6] Another Shia title is al-Muḥadditha, in view of the reports that angels spoke to Fatima on multiple occasions,[22][23][24] similar to Mary, mother of Jesus.[25]

Fatima is also recognized as Sayyidat Nisa' al-Janna (lit. 'mistress of the women of paradise') and Sayyidat Nisa' al-Alamin (lit. 'mistress of the women of the worlds') in Shia and Sunni collections of hadith, including the canonical Sunni Sahih al-Bukhari and Sahih Muslim.[7]

Fatima

The name Fatima is from the Arabic root f-t-m (lit. 'to wean') and signifies the Shia belief that she, her progeny, and her adherents (shi'a) have been spared from hellfire.[6][26][27] Alternatively, the word Fatima is associated in Shia sources with Fatir (lit. 'creator', a name of God) as the earthly symbol of the divine creative power.[28]

Kunyas

A kunya or honorific title of Fatima in Islam is Umm Abiha (lit. 'the mother of her father'), suggesting that Fatima was exceptionally nurturing towards her father.[29][30][31] Umm al-Aima (lit. 'the mother of Imams') is a kunya of Fatima in Twelver sources,[4] as eleven of the Twelve Imams descended from her.[32]

Early life

Fatima was born in Mecca to Khadija, the first of Muhammad's wives.[1] The mainstream Sunni view is that Khadija gave birth to Fatima in 605 CE, at age fifty, five years before the first Quranic revelations.[2] This implies that Fatima was over eighteen at the time of her marriage, which would have been unusual in Arabia.[2][3] Twelver sources, however, report that Fatima was born in about 612 or 615 CE,[2][33][34] when Khadija would have been slightly older.[35] The report of the Sunni Ibn Sa'd in his Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kubra suggests that Fatima was born when Muhammad was about thirty-five years old.[35]

The Sunni view is that Fatima had three sisters, named Zaynab, Umm Kulthum, and Ruqayyah, who did not survive Muhammad.[33] Alternatively, a number of Shia sources state that Zainab, Ruqayyah, and Umm Kulthum were adopted by Muhammad after the death of their mother, Hala, a sister of Khadija.[33][4] According to Abbas, most Shia Muslims hold that Fatima was Muhammad's only biological daughter,[33] whereas Fedele limits this belief to the Twelver Shia.[4] Hyder reports that this belief is prevalent among the Shia in South Asia.[36] Fatima also had three brothers, all of whom died in childhood.[37][38][39]

Fatima grew up in Mecca while Muhammad and his few followers suffered the ill-treatment of disbelievers.[40][3] On one occasion, she rushed to help Muhammad when filth was thrown over him at the instigation of Abu Jahl, Muhammad's enemy and a polytheist.[40][6] Fatima lost her mother, Khadija, in childhood.[41][6] When Khadija died, it is said that Gabriel descended upon Muhammad with a message to console Fatima.[3][6][42]

Marriage

Fatima married Muhammad's cousin, Ali, in Medina around 1 or 2 AH (623–5 CE),[42][14] possibly after the Battle of Badr.[43] There is Sunni and Shia evidence that some of the companions, including Abu Bakr and Umar, had earlier asked for Fatima's hand in marriage but were turned down by Muhammad,[44][14][45] who said he was waiting for the moment fixed by destiny.[3] It is also said that Ali was reticent to ask Muhammad to marry Fatima on account of his poverty.[14][31] When Muhammad put forward Ali's proposal to Fatima, she remained silent, which was understood as a tacit agreement.[14][46] On the basis of this report, woman's consent in marriage has always been necessary in Islamic law.[47] Muhammad also suggested that Ali sell his shield to pay the bridal gift (mahr).[48][14]

Muhammad performed the wedding ceremony,[3] and they prepared an austere wedding feast with gifts from other Muslims.[3][49][50] Shia sources have recorded that Fatima donated her wedding gown on her wedding night.[51][52] Later, the couple moved into a house next to Muhammad's quarters in Medina.[3][6] Their marriage lasted about ten years until Fatima's death.[53] Fatima's age at the time of her marriage is uncertain, reported between nine and twenty-one.[43][54][3][55] Ali is said to have been about twenty two.[55][56]

As with the majority of Muslims, the couple lived in severe poverty in the early years of Islam.[57][1] In particular, both had to do hard physical work to get by.[14][58] Shia sources elaborate that Ali worked at various jobs while Fatima was responsible for domestic chores.[59] It has also been related that Muhammad taught the couple a tasbih to help ease the burden of their poverty:[60] The Tasbih of Fatima consists of the phrases Allah-hu Akbar (lit. 'God is the greatest'), Al-hamdu-lillah (lit. 'all praise is due to God'), and Subhan-Allah (lit. 'God is glorious').[61] Their financial circumstances later improved after more lands fell to Muslims in the Battle of Khaybar.[14][1] Fatima was at some point given a maidservant, named Fidda.[14]

Following the Battle of Uhud, Fatima tended to the wounds of her father[62] and regularly visited the graves to pray for those killed in the battle.[3] Later, Fatima rejected Abu Sufyan's pleas to mediate between him and Muhammad.[62][3] Fatima also accompanied Muhammad in the Conquest of Mecca.[3]

Significance

Among others, the Sunni al-Suyuti (d. 1505) ascribes to Muhammad that, "God ordered me to marry Fatima to Ali."[14][51][56] According to Veccia Vaglieri and Klemm, Muhammad also told Fatima that he had married her to the best member of his family.[3][63] There is another version of this hadith in the canonical Sunni collection Musnad Ahmad Ibn Hanbal, in which Muhammad lauds Ali as the first in Islam, the most knowledgeable, and the most patient of the Muslim community.[64] Nasr writes that the union of Fatima and Ali holds a special spiritual significance for Muslims, as it is seen as the marriage between the "greatest saintly figures" surrounding Muhammad.[56]

Ali did not marry again while Fatima was alive.[65][45] However, al-Miswar ibn Makhrama, a companion who was nine when Muhammad died, appears to be the sole narrator of an alleged marriage proposal of Ali to Abu Jahl's daughter in Sunni sources. While polygyny is permitted in Islam, Muhammad reportedly banned this marriage from the pulpit, saying that there can be no joining of the daughter of the prophet and the daughter of the enemy of God (Abu Jahl). He is also said to have praised his other son-in-law, possibly Uthman or Abu al-As. Soufi notes that the reference to the third caliph Uthman might reflect the Sunni orthodoxy, in which Uthman is considered superior to his successor Ali.[66]

Buehler suggests that such Sunni traditions that place Ali in a negative light should be treated with caution as they mirror the political agenda of the time.[14] In Shia sources, by contrast, Fatima is reported to have had a happy marital life, which continued until her death in 11 AH.[51] In particular, Ali is reported to have said, "Whenever I looked at her [Fatima], all my worries and sadness disappeared".[51]

Appearance

The Sunni al-Hakim al-Nishapuri (d. 1014) and al-Khwarazmi (d. 1173[67]), and the Shia al-Qadi al-Nu'man (d. 974) and al-Tabari al-Shia (eleventh century[68]), have likened Fatima to the full moon, the sun hidden by clouds, or the sun that has come out of the clouds. The first expression is a common metaphor for beauty in Arabic and Persian. The Shia al-Majlesi (d. 1699) explains that the second expression is a reference to Fatima's chastity, while the third expression refers to her primordial light.[69]

Soufi details that Fatima's manners closely resembled Muhammad's.[8] Her gait was also similar to the prophet's, according to Veccia Vaglieri, who also argues that Fatima must have enjoyed good health on the account of bearing multiple children, her arduous house chores, and her journeys to Mecca.[3] Her sources are silent about the appearance of Fatima, which leads her to the conclusion, "Fatima was certainly not a beautiful woman".[3] In contrast, the Sunni al-Khwarazmi relates from the prophet that, "If beauty (husn) were a person, it would be Fatima; indeed she is greater," while some Shia authors have likened her to a human houri.[70][10]

Death

Fatima died in 11/632, within six months of Muhammad's death.[14][166] She was 18 or 27 years old at that time according to Shia and Sunni sources, respectively.[33] The exact date of her death is uncertain but the Shia commonly commemorates her death on 13 Jumada II.[167] The Sunni belief is that Fatima died from grief after Muhammad's death.[3][4] Shia Islam, however, holds that Fatima's injuries during a raid by Umar directly caused her miscarriage and death shortly after.[14][4][137]

Al-Tabari mentions the suffering of Fatima in her final days.[13] Shia traditions similarly describe Fatima's agony in her final days.[168] In particular, the Isma'ili jurist al-Nu'man similarly reports a hadith from the fifth Imam to the effect that "whatever had been done to her by the people" caused Fatima to become bedridden, while her body wasted until it became like a specter.[169] This hadith seems to contain a reference to Fatima's injuries during the raid.[169] Ayoub describes Fatima a symbol of quiet suffering in Islamic piety.[170] In particular, the Twelver Shia believe in the redemptive power of the pain and martyrdom endured by the Ahl al-Bayt, including Fatima, for those who empathize with their divine cause and suffering.[21][171][172]

Multiple sources report that Fatima never reconciled with Abu Bakr and Umar,[134][173][107][15] partly based on a tradition to this effect in the canonical Sunni collection Sahih al-Bukhari.[174][175] There are some accounts that Abu Bakr and Umar visited Fatima on her deathbed to apologize, which Madelung considers self-incriminatory.[134] As reported in al-Imama wa al-siyasa,[176] Fatima reminded the two visitors of Muhammad's words, "Fatima is part of me, and whoever angers her has angered me."[13][176] The dying Fatima then told the two that they had indeed angered her, and that she would soon take her complaint to God and His prophet, Muhammad.[75][177] There are also Sunni reports that Fatima reconciled with Abu Bakr and Umar, though Madelung suggests that they were invented to address the negative implications of Fatima's anger.[134]

- Reference: /en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fatima

What is Sufism?

What is Sufism?

An excerpt from Living Presence: A Sufi Way to Mindfulness & the Essential Self

Sufism is a spiritual path based on the principles expressed in the Holy Qur’an and embodied in the character of the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him. Sufism is a practice and way of life in which a deeper identity is discovered and lived. This deeper identity, or essential Self, is beyond the superficial personality and is in harmony with the Source of Life. The essential Self has abilities of awareness, action, creativity, and love that are far beyond those of the superficial personality. Eventually, it is understood that these abilities belong to a greater Being that we each individualize and embody in our own unique way while never being separate from it.

Islam originally meant submission: the harmonization of the individual self with the Divine. Sufism is an intentional, intensified expression of that universal state of submission, which could be called Islam. More than a doctrine or a belief system, Sufism is an experiential approach to the Divine. It is a tradition of enlightenment that carries the essential truth forward through time. Tradition, however, must be conceived in a vital and dynamic sense. Its expression must not remain limited to the religious and cultural forms of the past. The truth of Islam requires reformulation and fresh expression in every age.

This Tradition is and will remain a critic of worldliness, of everything that causes us to be forgetful of the Divine Reality. It will never compromise with a stubbornly materialistic society. It is and must be a way out of the labyrinth of a bankrupt materialistic culture. Most important, however, it is an invitation to meaningfulness and well-being.

Islam, as we know it today, developed within an historical and cultural matrix. The Islamic revelation presented itself as the latest expression of the essential message brought to humanity by the prophets of all ages. The Qur’an recognizes the validity of countless prophets, or messengers, who have come to awaken us from our selfish egoism and remind us of our spiritual nature. It confirmed the validity of past revelations, while asserting that the original message was often distorted over the course of time.

Islam’s claim to universality is founded on the broad recognition that there is only one God, the God of all people and all true religions. Islam understands itself to be the wisdom realized by the great prophets—explicitly including Jesus, Moses, David, Solomon, and Abraham, among others, and implicitly including other unnamed enlightened beings of every culture.

Over fourteen centuries the broad Islamic tradition has contributed a body of spiritual literature second to none on earth. The guiding principles of the Qur’an, and the heroic virtue of Muhammad and his companions provided an impetus that allowed a spirituality of love and consciousness to flourish. Those who follow the path today are the inheritors of an immense treasure of wisdom and literature.

Beginning from its roots at the time of Muhammad, Sufism has organically grown like a tree with many branches. These branches generally do not see one another as rivals. In the world today diverse groups exist under the name of Sufism. There are those who accept Islam in both form and essence, while there are others who are Muslim in essence but not in strictly orthodox form.

If Islam recognizes one central truth, it is the unity of being, that we are not separate from the Divine. This is a truth that our age is in an excellent position to appreciate—emotionally, because of the shrinking of our world through communications and transportation, and intellectually, because of developments in the sciences. We are One: one people, one ecology, one universe, one being. If there is a single truth, worthy of the name, it is that we are all integral to the Truth, not separate. The realization of this truth has its effects on our sense of who we are, on our relationships to others and to all aspects of life. The essence of Islam is about realizing the current of love that runs throughout all life, the unity behind forms.

If Sufism has a central method, it is the development of remembrance and love of God. Only presence can awaken us from our enslavement to the world and our own psychological processes, and only cosmic love can comprehend the Divine. Love is the highest activation of intelligence, for without it nothing great would be accomplished, whether spiritually, artistically, socially, or scientifically.

Islam, the state of submission, is the attribute of those who love. Lovers are people who are purified by love, free of themselves and their own qualities and fully attentive to the Beloved. This is to say that Sufis are not held in bondage by any quality of their own because they see everything they are and have as belonging to the Source. An early Sufi, Shebli, said “The Sufi sees nothing except God in the two worlds.”

This book is about one essential aspect of the spiritual life: presence, and how this presence can develop into remembrance, and how through remembrance our essential human qualities can be activated.

Abu Muhammad Muta‛ish says: “The Sufi is he whose thought keeps pace with his foot, i.e., he is entirely present: his soul is where his body is, and his body where his soul is, and his soul where his foot is, and his foot where his soul is. This is the sign of presence without absence. Others say on the contrary: ‛He is absent from himself but present with God.’ It is not so: he is present with himself and present with God.”

We live in a culture that has been described as materialistic, alienating, neurotically individualistic, narcissistic, and yet ridden with anxiety, shame, and guilt. From the Sufi point of view, humanity today is suffering under the greatest tyranny, the tyranny of the ego. We worship innumerable false idols, but all of them are forms of the ego.

There are many ways for the human ego to usurp even the purest spiritual values. The true Sufi is the one who makes no personal claims to virtue or truth, but who lives a life of presence and selfless love. More important than what we believe is how we live. If certain beliefs lead to exclusiveness, self-righteousness, and fanaticism, it is the vanity of the believer that is the problem. If the remedy increases the sickness, an even more basic remedy is called for.

The idea of presence with love may be the most basic remedy for the prevailing materialism, selfishness, and unconsciousness of our age. In our obsession with our false selves, in turning our backs on God, we have also lost our essential Self, our own divine spark. In forgetting God, we have forgotten ourselves. Remembering God is the beginning of remembering ourselves.

- Reference: The Threshhold Society: Published by Tarcher-Penguin, Inc.

Religious restrictions around the world

Religious restrictions around the world

For more than a decade, Pew Research Center has been tracking global patterns in restrictions on religion – both those imposed by governments and hostilities committed by individuals and social groups. Scroll down to explore restrictions in 198 countries and territories, and see how each country’s restrictions have changed since 2007.

In this scatter plot, each square represents a country. A square’s placement indicates the severity of restrictions in that country on the Government Restrictions Index (GRI) and the Social Hostilities Index (SHI). The color of each square represents its region of the world.

In 2021, four countries – Afghanistan, Egypt, Pakistan and Syria – had “very high” levels of both government restrictions and social hostilities involving religion. In Afghanistan, the Taliban seized control of the country in 2021 and targeted religious minorities and others who did not follow their stricter interpretations of Islamic law. And in Pakistan, religious minorities such as Shiite Hazaras (who are also an ethnic minority) and Ahmadi Muslims were killed in multiple targeted attacks by individual assailants or militant groups.

Each country’s GRI and SHI sc

Each country’s GRI and SHI score measures change annually in response to events within a country. From 2007 to 2021, Egypt’s GRI and SHI scores have been “high” or “very high,” as shown in this example.

Globally, Government Restrictions on Religion Reached Peak Levels in 2021, While Social Hostilities Went Down

14th annual report includes a look at countries that restrict religious practices and grant benefits to religious groups at the same time

In 2021, government restrictions on religion – laws, policies and actions by state officials that limit religious beliefs and practices – reached a new peak globally, according to Pew Research Center’s latest analysis of government restrictions and social hostilities involving religion in 198 countries and territories around the world.

Harassment of religious groups and interference in worship were two of the most common forms of government restrictions worldwide in 2021.

Among the study’s key findings:

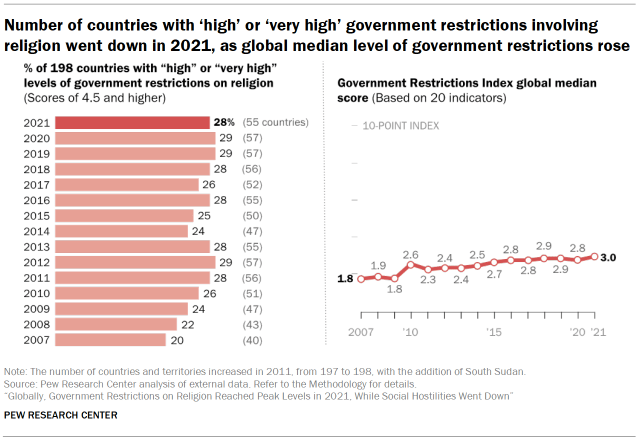

- The global median level of government restrictions on religion ticked up to 3.0 in 2021 from 2.8 in 2020 on the Government Restrictions Index, a 10-point scale of 20 indicators. This was the highest global median score since we began tracking restrictions in 2007.

- 55 countries (28% of the total) had “high” or “very high” levels of government restrictions in 2021, down slightly from 57 countries (29%), a level reached in 2020, 2019 and 2012. (The median index score for all countries rose anyway, partially because there were slightly more increases in index scores than decreases among the 198 countries and territories analyzed.)

- Religious groups faced harassment by governments in 183 countries in 2021, the largest number since the study began. Governments interfered in worship in 163 countries, down slightly from 164 in 2020 but still close to the all-time high.

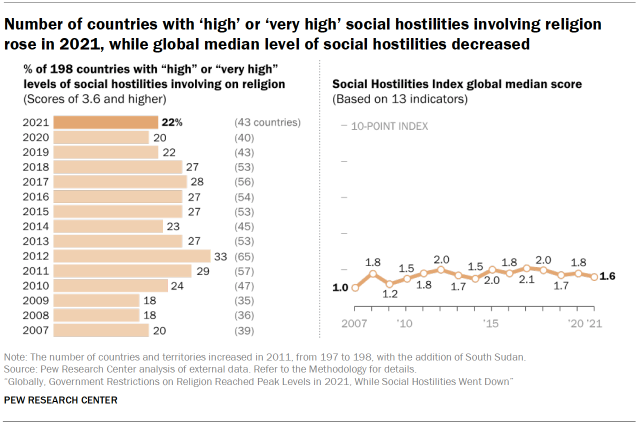

- The global median level of social hostilities involving religion – including violence and harassment by private individuals, organizations or groups – fell from 1.8 in 2020 to 1.6 in 2021 on the Social Hostilities Index, a 10-point scale composed of 13 indicators.

- 43 countries (22% of all studied) had “high” or “very high” levels of social hostilities in 2021, up from 40 countries (20%) in 2020 but still closer to the low point (18%) than to the high point (33%) previously recorded over the course of the study.

This report examines these and other findings from Pew Research Center’s 14th annual study of restrictions on religion around the world, including changes in the index scores at the global and re

regional levels. It also includes a section showing that governments in most countries simultaneously impose restrictions on religion and grant benefits to religious groups.

Some background on the study

Each year since 2007, Pew Research Center has tracked government restrictions and social hostilities on two 10-point indexes:

- The Government Restrictions Index (GRI): Government restrictions on religion include laws, policies and actions that regulate and limit religious beliefs and practices. They also include policies that single out certain religious groups or ban certain practices; the granting of benefits to some religious groups but not others; and bureaucratic rules that require religious groups to register to receive benefits.

- The Social Hostilities Index (SHI): Social hostilities include actions by private individuals or groups that target religious groups; they also include actions by groups or individuals who use religion to restrict others. The SHI captures events such as religion-related harassment, mob violence, terrorism/militant activity, and hostilities over religious conversions or the wearing of religious symbols and clothing.

Government restrictions have increased gradually over time since 2007, when the global median level on the GRI was 1.8.

Social hostilities – which capture incidents that are more likely to vary from year to year – have seen more fluctuations. On the SHI, the global median score started at 1.0 in 2007, reached a peak of 2.1 in 2017, and fell to 1.6 in 2021.

Countries with ‘high’ and ‘very high’ government restrictions and social hostilities in 2021

Another way to examine restrictions and hostilities involving religion is to look at the number of countries in the “high” or “very high” categories on each index.

In 2021, 28% of countries had “high” or “very high” levels of government restrictions, a slight decline from 29% in 2020.

Meanwhile, fewer countries (22%) had “high” or “very high” levels of social hostilities.

The majority of countries in the study had “moderate” or “low” levels of government restrictions and social hostilities.

Government harassment of religious groups, interference in worship in 2021

Two measures – government harassment of religious groups and government interference in worship – have contributed to the GRI scores in most of the countries analyzed.

Government harassment can include a wide range of actions or offenses, from the use of physical force targeting religious groups to derogatory comments by government officials. It can also include laws and policies that single out groups or make religious practice more difficult.

In 2021, governments harassed religious groups in 183 countries (92% of countries analyzed), up from 178 countries in 2020. This type of restriction was widespread across all five regions we analyzed. For example, at least one case of government harassment was reported in each of the 20 countries in the Middle East-North Africa region. The same was true for 43 of 45 countries in Europe (96%), 33 of 35 countries in the Americas (94%), 44 of 48 countries in sub-Saharan Africa (92%) and 43 of 50 countries in the Asia-Pacific region (86%).

In Europe, for example, Geert Wilders, who leads the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands (a party that held seats in government in 2021 and went on to win more seats in 2023), called for the “de-Islamization” of the country on Twitter (now known as X). He also proposed “a series of measures including closing all mosques and Islamic schools, banning the Quran, and barring all asylum seekers and immigrants from Muslim-majority countries,” according to the U.S. State Department. (Statements targeting religious minorities and asylum seekers are not new in either the country or in the region and were detailed in our report looking at restrictions in 2016.)

In the Americas, the government of Nicaragua has targeted Catholic clergy for supporting the country’s pro-democracy movement, according to the U.S. State Department. The president and the vice president (who is also the first lady) called priests and bishops “terrorists in cassocks” and “coup-plotters.” Meanwhile, a member of the National Assembly, Wilfredo Navarro Moreira, called a cardinal and several bishops “servants of the devil” in a television interview.

Other government harassment activities measured on the GRI include policies that make religious practices more difficult – such as restrictions on religious dress, which tend to affect Muslim women, and laws limiting halal or kosher meat production, which generally affect Muslims and Jews.

In several European countries, for example, authorities in recent years have imposed bans on headscarves or full-face veils that tend to affect Muslim women, even as exceptions are sometimes made for people who wear them for nonreligious reasons.

Austria, for example, forbids full-face coverings unless they are worn for “artistic, cultural, or traditional events, in sports, or for health or professional reasons.” Face coverings such as women’s burqas and niqabs are also banned in Denmark.

In addition, Denmark does not allow the slaughter of animals for meat unless the animals are stunned before being killed, a restriction that makes it harder for Jews and Muslims to follow their religions’ dietary guidelines. (Kosher and halal meat can be imported from other European Union countries, but Jews and Muslims have expressed frustration about the law.)

Governments interfered in worship in 163 countries (82% of countries in the study) in 2021, down from a peak of 164 in 2020. Our definition of government interference in worship includes laws, policies and actions that disrupt religious activities, the withholding of permits for such activities, or denying access to places of worship. This measure also includes restrictions on practices and rituals that may not be specifically tied to worship, such as burial practices and conscientious objection to military service for religious reasons.1

As with government harassment, there was at least one report of government interference in worship in every country in the Middle East-North Africa region, along with 91% of countries in Europe, 81% in sub-Saharan Africa, 80% in the Americas and 70% in Asia and the Pacific.

For example, in the Maldives, where Islam is the state religion, non-Muslim groups are forbidden to build places of worship or practice their faith publicly. Similarly, Egyptian law allows only members of recognized religious groups (Sunni Islam, Christianity and Judaism) to express their faith in public and construct houses of worship.

In 2021, cases of government interference in worship also included the use of force against religious leaders who violated COVID-19 restrictions. In some countries, religious groups claimed (as they had in 2020) that public health measures were unevenly or unfairly applied to their activities and places of worship, particularly in comparison with businesses like shops and restaurants.

In Canada, three churches that were fined for defying lockdown measures in British Columbia filed a legal challenge in 2021 against public health orders that limited religious gatherings, according to the U.S. State Department. The churches contended that there were fewer restrictions on restaurants and other businesses, as well as on Orthodox Jewish synagogues that were allowed to hold indoor services. In addition, several Canadian clergy were fined and arrested after holding in-person services that violated public health measures.

Government restrictions and government benefits

This section analyzes how many countries have governments that provide benefits to religious groups and, at the same time, harass religious groups and interfere in worship.

Here’s what we found in 2021:

- In 127 countries, governments provided funds or other resources for religious education.

- In 107 countries, governments gave funds or other resources for religious buildings, such as for construction, upkeep or maintenance of houses of worship.

- In 67 countries, governments provided benefits to clergy, such as salaries, exemptions from military service, or access to certain government jobs (such as military or prison chaplaincies).2

Overall, governments in 161 countries provided at least one of these benefits to religious organizations. Yet, at the same time, governments in most of these countries also harassed religious groups (149 countries) and/or interfered in worship (134 countries).

Our data did not allow us to discern why countries grant benefits to religious groups, for example, whether governments hope that paying the salaries of clergy will lead those clergy to deliver sermons that align with government views. So we cannot say whether specific governments are attempting to manipulate, entice or co-opt religious groups with incentives.

Still, the analysis adds a layer of complexity to the relationship between governments and religious groups. For example, it shows that some governments that provide benefits to clergy also, at the same time, seek to restrict and control these clergy – for example by directly restricting what they can say in sermons.

Funds for religious education

In 2021, governments in 127 countries gave money to religious education initiatives in their countries. This included payments for teachers’ salaries at religious schools or subsidies for the schools more broadly.

In Trinidad and Tobago, for example, the government gave money to “religiously affiliated public schools” run by Christians, Hindus and Muslims. The government also provided most construction costs for these schools.

In the Netherlands, the government funded religious schools and “other religious educational institutions” if they satisfied certain education requirements and complied with guidelines regarding class sizes. And in Sweden, the government helped fund independent religious schools through a voucher system; the schools had to abide by national curriculum guidelines.

In Singapore, even though the country does not generally allow religious education in public schools, there were 57 “government-subsidized religiously affiliated schools” in 2021. According to the sources used in this study, most of these schools were Christian; three were Buddhist.

Funds and tax exemptions for religious property

In 107 countries, governments gave property-related benefits to religious groups in 2021, often through direct subsidies or tax exemptions.

In Malaysia, a federal entity devoted to Islamic affairs provided funds for mosque projects. While no funds were specifically allocated for non-Muslim groups, temples and churches also received funding, according to the U.S. State Department’s International Religious Freedom Report. And from December 2020 to May 2021, 1,145 Hindu temples received Malaysian government funding.

In Germany, state governments provided funds to renovate and build synagogues. In the state of Baden-Wuerttemberg, the local government also signed a contract in 2021 with Jewish communities to provide funds for security for synagogues and for the establishment of a Jewish academy.

In Angola, registered religious groups did not have to pay some property taxes. And in Gabon, registered religious groups were exempt from fees for land-use and construction permits.

In some cases, governments provided resources to historically significant religious sites. For example, the Egyptian government, “in a potential boost to religious tourism,” worked to restore many historic sites important to Christians, Jews and Shiite Muslims.

Government benefits to clergy

In addition, our analysis showed that 67 countries gave government benefits specifically to clergy – including payments of salaries, exemption from military service, and access to certain government positions like military and prison chaplaincies – in 2021.

The most common type of benefit to clergy in 2021 was payment of salaries (found in 42 of the 67 countries). In Jordan, for example, a government agency called the Ministry of Awqaf (religious endowments), managed mosques in the country and provided salaries for their staffs. In Algeria, the government provided salaries and benefits for religious personnel of mosques and churches. And in Iceland, in 2021, the Evangelical Lutheran Church received government funds to pay for its staff’s salaries and benefits.

Sometimes clergy receive legal benefits from the government. In Honduras, for instance, high-ranking clergy in many religious groups are exempt from court subpoenas. And in Canada, clergy who are part of religious groups with nonprofit status receive benefits such as a “housing deduction” and “expedited processing through the immigration system.”

In 36 countries, only clergy who are associated with a religion that is favored or preferred by the government – either through official status or various types of preferential treatment – received these types of benefits in 2021.

In Peru, for example, the constitution recognizes the Catholic Church as having an important role in the country, while a concordat with the Vatican allows the Church “certain institutional privileges in education, taxation, and immigration of religious workers.” The military hires only Catholic chaplains, Catholicism is taught in religion classes at public schools, and Catholic bishops must approve the teachers who teach these classes.

Restrictions in these countries

In most of the countries that provide benefits to religious groups or clergy, the government also harassed some religious groups or interfered in worship in 2021.

For instance, in Sunni-majority Saudi Arabia, where the government funds the construction of most Sunni mosques and gives a monthly stipend to imams at the mosques, sermons are restricted by the Ministry of Islamic Affairs, which directs the imams to choose from an approved list. The content is not permitted to be “sectarian, political or extremist, promoting hatred or racism, or including commentary on foreign policy,” according to the U.S. State Department. Ministry officials have authority to attend sermons to ensure imams don’t preach about forbidden topics.

The Saudi government also has targeted Sunni clerics (along with Shiite clerics) when they express religious views deemed unacceptable by the government. One Sunni cleric, Hassan Farhan al-Maliki, remained in prison without due process for “allegedly calling into question the fundamentals of Islam,” according to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. He was charged with 14 crimes and has been in prison since 2017.

A similar situation exists in Jordan, where the government both pays the salaries of mosque employees across the country and forces imams to stick to selected themes for their Friday sermons. Imams who do not follow these guidelines can be fined, suspended, imprisoned or forbidden from giving Friday sermons.

In Ethiopia, where the government funded 219 Islamic schools and 250 Catholic schools in 2021, government security forces used tear gas against crowds of thousands of Muslims who had gathered in Addis Ababa for a Grand Iftar event during the Islamic holy month of Ramadan.

In Austria, where buildings used by recognized groups for religious purposes are exempt from property taxes, a new anti-terrorism law allows officials to more easily shut down mosques to “protect public security.”

Pew Research Center has conducted other analyses of relationships between governments and religious groups, outside the scope of the annual restrictions reports. For example, in 2017 we published a report on countries with official state religions, and in 2019, we examined the tradition of “church taxes” in Western Europe.

March 5, 2024: Pew Research Center

The Historical Context of The Bhagavadgita

The Historical Context of The Bhagavadgita

The Bhagavad Gita is perhaps the most famous, and definitely the most widely-read, ethical text of ancient India. As an episode in India's great epic, the Mahabharata, The Bhagavad Gita now ranks as one of the three principal texts that define and capture the essence of Hinduism; the other two being the Upanishads and the Brahma Sutras. Though this work contains much theology, its kernel is ethical and its teaching is set in the context of an ethical problem.

The teaching of The Bhagavad Gita is summed up in the maxim "your business is with the deed and not with the result." When Arjuna, the third son of king Pandu (dynasty name: Pandavas) is about to begin a war that became inevitable once his one hundred cousins belonging to the Kaurava dynasty refused to return even a few villages to the five Pandava brothers after their return from enforced exile, he looks at his cousins, uncles and friends standing on the other side of the battlefield and wonders whether he is morally prepared and justified in killing his blood relations even though it was he, along with his brother Bhima, who had courageously prepared for this war. Arjuna is certain that he would be victorious in this war since he has Lord Krishna (one of the ten incarnations of Vishnu) on his side. He is able to visualize the scene at the end of the battle; the dead bodies of his cousins lying on the battlefield, motionless and incapable of vengeance. It is then that he looses his nerve to fight.

The necessity for the arose because the one hundred cousins of the Panadavas refused to return the kingdom to the Pandavas as they had originally promised. The eldest of the Pandav brothers, Yudhisthir, had lost his entire kingdom fourteen years ago to the crafty Kaurava brothers in a game of dice, and was ordered by his cousins to go on a fourteen-year exile. The conflict between the Pandavas and the Kauravas brewed gradually when the Kauravas refused to return the kingdom to the Panadavas and honor the agreement after the fourteen-year exile, and escalated to a full scale war when the Kauravas refused to even grant Yudhisthir's reduced demand for a few villages instead of the entire kingdom.

As the battle is about to begin, Arjuna, himself an acclaimed warrior, wonders how he could kill his own blood relatives with whom he had grown up as a child. He puts the battle on hold and begins a conversation with Krishna, one of the ten but most important incarnations of the Universal Hindu God, Vishnu. The Bhagavad Gita begins here and ends with Krishna convincing Arjuna that in the grand scheme of things, he is only a pawn. The best he could do is do his duty and not question God's will. It was his duty to fight. In convincing Arjuna, the Lord Krishna provides a philosophy of life and restores Arjuna's nerve to begin the battle -- a battle that had been stalled because the protagonist had lost his nerve and needed time to reexamine his moral values.

Even though The Bhagavad Gita (hereafter referred to as the Gita) is one of the three principal texts that define the essence of Hinduism, and since all over the world Hindus chant from the Gita during most of their religious ceremonies, strictly speaking the Gita is not one of the Hindu scriptures. In light of its inseparable links to one of the two great Hindu epics (Mahabharata and Ramayana) which most Indians hold very dear to their hearts, and because Krishna, the most venerated and popular of the incarnations of Lord Vishnu, figures so prominently in it, the Gita over the years has not only become very popular but has ascended to spiritual heights that are afforded only to the Vedas (and the subsequent reinterpretive philosophies that followed them) and the Upanishads in the ancient Indian literature.

The concept and symbol of God were extremely complicated issues (see below) in the ancient Hindu religious literature prior to the writing of the Gita. The notion of God and the paths to salvation are integral parts of all religions. The manner in which Hinduism originally dealt with these two fundamental issues was very complex and appeared to be too speculative at times. This was one of the reasons for which Buddhism branched out as a separate religion. When Buddhism was beginning to grow in popularity, Hinduism met with its first challenge: To provide a clear-cut, easy-to-worship symbol of God to its followers. For a variety of reasons, Lord Krishna was the obvious choice. Many have even suggested that it was one of the most pivotal choices ever made by ancient scholars to `humanize' the concept of God in the Hindu religion. Molded in the original image of Lord Vishnu, Krishna is an affable Avatar (reincarnation of God) which for the first time provided concrete guidelines for living to all mortals. The average Hindu might not know much about Brahma, but every one knows who Lord Krishna is. Mahatma Gandhi read the Gita often when he was in seclusion and in prison.

But, the universal popularity of the Gita has not detracted Indian scholars from deviating from the fundamental truth about Hinduism. The Gita is not the Hindu scripture even though the literal translation of "Bhagavad Gita" is "The Song of God". The Nobel laureate Indian poet, Rabindra Nath Tagore, rarely quoted from the Gita in his philosophical writings; instead, he chose to refer to the Upanishads, to quote from it, and to use its teachings in his own works. Of course, the teachings of the Upanishads are included in the Gita; they are visible in multiple chapters of the Gita. The kinetic concepts of karma and yoga, which appeared for the first time in the Upanishads (explained below), appear repeatedly in the Gita, often in disguised forms.

As with almost every religious Indian text, it is difficult to pinpoint when exactly the Gita was written. Without a doubt, it was written over a period of centuries by many writers. From the contents of the Gita, it is abundantly clear that both the principal teachings of the Upanishads and of early Buddhism were familiar to the writers of the Gita. So, it has been approximated that the Gita was written during the period 500-200 BCE. Even though India is one of the few nations which has a continuous documented history, very few Indian religious texts exists for which the exact date of publication is established without controversy.

Despite its universal appeal, the Gita is replete with contradictions both at the fundamental level and at the highest level of philosophical discourse. To the discerning eye, it would seem that what has been said in the previous chapter, is contradicted in the very next chapter. This is the fundamental complaint against the Gita, and this fact would appear to be ironic given the fact that the Gita was originally written to reconcile the differences between two of the six major ancient Indian philosophies (Darshans) that evolved over the early years of Hinduism and became integral parts of ancient Indian religious literature. The irony disappears however when one understands what the Gita purported to achieve at the level of philosophical and religious discourse. This fact is crucial not only for the understanding of the principal themes of the Gita but also to locate the essence of the Gita in the overall picture of ancient Indian doctrines. The Gita attempted, for the first time, to reconcile the teachings of two very abstract Indian religious doctrines into one whole. The task was a formidable one.

The Gita tried to include the fundamentals of two ancient Indian philosophies into one document and reconcile the principal differences between them. At the outset, one must note that the two doctrines (Darshans) were often extremely difficult to understand. Hence the inevitable contradictions or duality of interpretation. The Six Darshans of ancient India were actually of differing origin and purpose, but all were brought into the scheme by being recognized as viable ways of salvation. They were divided into three groups of two complementary schools of thought (Darshans) or doctrines: Nyaya and Vaisesika; Sankhyya and Yoga; and Mimamsha and Vedanta. The Bhagavad Gita attempted to reconcile the Sankhyya philosophy with those of the Vedanta doctrine. One must note in passing that the Sankhyya school of thought led to Buddhism while the Vedanta philosophy is at the root of modern Hinduism. In this article, we are only going to discuss briefly the two Darshans -- the Sankhyya and the Vedanta -- the Gita attempted to reconcile.

The Sankhyya is the oldest of the six Darshans while the Vedanta is the most important of the six systems. The various subsystems of the Vedanta doctrine has led to the emergence of modern intellectual Hinduism. The primary text of the Vedanta system is the Brahma Sutras, and its doctrines were derived in great part from the Upanishads, which marked the beginning of Hinduism as is understood and practiced today. Even though the Vedas are India's ancient sacred texts, modern Hinduism begins with the Vedanta (end of Vedas) and attains its zenith with the Brahma Sutras.

The Sankhyya philosophy traces the origins of everything to the interplay of Prakriti (nature) and Purusha (the Self, to be differentiated from the concept of the soul in the latter Indian philosophies). These two separate entities have always existed and their interplay is at the root of all reality. The concept of God is conspicuous by its absence. There is no direct mention of God but only a passing reference as to how one should liberate himself to attain the realization of Is war (a heavenly entity). A very significant feature of Sankhyya is the doctrine of the three constituent qualities (gunas), causing virtue (sattva), passion (rajas), and dullness (tamas). On the other hand, the Vedanta school of thought deals with the concept of Brahman the ultimate reality that is beyond all logic and encompasses not only the concepts of being and non-being but also all the phases in between. It is one of the most difficult concepts in the entire Indian philosophy. At the highest level of truth, the entire universe of phenomena, including the gods themselves, was unreal -- the world was Maya, illusion, a dream, a mirage, a fragment of the imagination. The only reality is Brahman.

One can see quite clearly the sources for the Gita's contradictions. It was dealing with not only two widely-differing Darshans but also with two of the most abstract philosophical systems. We know that the Gita was written long after the emergence of modern Hinduism. So it was able to draw on a wide variety of philosophical themes -- both ancient and relatively modern by comparison, and often opposing -- still present in modern Hinduism. Yet, to consolidate the two schools of thoughts proved to be an extremely difficult task -- a fact which the lyricism of the Gita, in the words of Lord Krishna himself, could not camaflouge. Any serious reader would arrive at the conclusion that even though the Gita mentions the Sankhyya, it more or less elaborates on ideas that originated with the Upanishads.

The fundamental tenets of Hinduism took shape during the period 800-500 BCE. They were set down in a series of treaties called the Upanishads. The Upanishads arise at the end of the Vedas, which earns it the name Veda-anta, which literally means "end (anta) of the Vedas." Almost all philosophy and religion in India rests upon the wealth of speculation contained in these works. The Upanishads center on the inner realms of the spirit. Encompassing the meaning of spiritual unity, the Upanishads point directly to the Divine Unity which pervades all of nature and is identical to the self.

There are four "kinetic ideas" -- ideas that involve action or motion -- that represent the core of Indian spirituality. The ultimate objective is control of the passions and to realize a state of void -- a concept very similar to that of Buddhism. The four kinetic ideas are "karma, maya, nirvana, and yoga" and they appear in the Gita. But one must remember that they appeared for the first time in the Upanishads. A brief summary of the four ideas are provided below.

Karma: The law of universal causality, which connects man with the cosmos and condemns him to transmigrate -- to move from one body to another after death -- indefinitely. In the Gita, Krishna makes an allusion to the eternal soul that moves from body to body as it ascends or descends the ladder of a given hierarchy, conditioned on the nature of one's own karma -- work of life or life deeds.

Maya: refers to cosmic illusion; the mysterious process that gives rise to phenomena and maintains the cosmos. According to this idea, the world is not simply what is seems to the human senses -- a view with which the 20th century western scientists wholly agree. Absolute reality, situated somewhere beyond the cosmic illusion woven by maya and beyond human experience as conditioned by karma. Both Tagore, the renowned Indian poet and Albert Einstein, the famous scientist, agreed on this conclusion. Absolute reality, in their minds, was beyond human perception.

Nirvana: The state of absolute blessedness, characterized by release from the cycle of reincarnations; freedom from the pain and care of the external world; bliss. Union with God or Atman. Hindus call such mystical union with ultimate reality as Samandhi or Moksha.

Yoga: implies integration; bringing all the faculties of the psyche under the control of the self. Essentially, the object of various types of yoga is mind control, and the system lays down the effectual techniques of gaining liberation and achieving divine union. The word yoga is loosely applied to any program or technique which leads toward the union with God or Atman. There are five principal kinds of yoga: Hatha(physical), jnana (the way of knowledge), bhakti (the way of love), karma (the way of work), and rajah (mystical experience).

The Western world's interest in The Bhagavad Gita began around the end of the eighteenth century when the first English translation of the Gita was published. All religious texts of ancient India were written in Sanskrit. In November 1784, the first direct translation of a Sanskrit work into English was completed by Charles Wilkins. The book that was translated was The Bhagavad Gita. Friedreich Max Mueller (1823-1900), the German Sanskritist who spent most of his working life as Professor of Comparative Philology at Oxford University, served as the chief editor of the Sacred Books of the East. (Oxford University Press). The Gita was included in this famous collection. Since then, the Gita has become one of the most widely-read texts of the world. True, there are unexplained contradictions and paradoxes in this brief book, but its wide-ranging implications based on the two ancient Darshans of India and its allegorical meanings are still being examined and reinterpreted.

Articles-Latest

- Koran burning conviction sparks fury as blasphemy law 'returns to UK'

- Robert Francis Prevost - Pope Leo XIV

- Pope Francis' death follows recent health challenges. Here's what we know about how he died.

- Easter April 2025 - international Celebrations

- The Rule of the twelve psalms -Worthy is the Lamb

- Religion in Africa Before Christianity and Islam

- 6 The Origin of Yahweh

- Dumo Di Milano

- What Did the Crow Tribe Believe In: Discover The Beliefs!

- 7 Reasons Historic Christianity Rejects the Book of Enoch

- 8 Breathtaking Mountain Monasteries Around the World

- Ethiopian Bible is oldest and most complete on earth

- Muhammad Muhammad was a prophet and founder of Islam.

- World Day of the Poor – SVP Christmas Campaign 2024

- Pope Francis to open 5 sacred portals on Christmas Eve — for a ritual that’s never been done before

- The 144,000 in Revelation

- Over 73 dead bodies 'used for meditation', 600 crocs in a pond, found in two Thai temples

- Occultism: Western Occult Tradition

- What is a Mudra

- Blood Sacrifices: Ancient Rituals of Life and Death

Articles-Most Read

- Home

- Let There Be Light

- Plants that feel and Speak

- The Singing Forest

- The Singing Forest-2

- Introduction

- Meditation

- Using Essential Oils for Spiritual Connection

- Heaven Scent

- Plants that Feel and Speak-2

- Purification

- Making the Spiritual Connection

- Anointing

- Essential Oils: The unseen Energies

- The Sanctity of Plants

- The Aroma Of Worship - Introduction

- The Aroma Of Worship-Foreward

- Methods Of Use

- Spiritual Blending

- Handling and Storage