Pilgrims yearn to visit isolated peninsula where Catholic saints cared for Hawaii's leprosy patients

Pilgrims yearn to visit isolated peninsula where Catholic saints cared for Hawaii's leprosy patients

Kalaupapa beckoned to Kyong Son Toyofuku. She had long prayed to visit the hard-to-reach Hawaiian peninsula, trapped by its deep-green, sheer sea cliffs and rugged, black rock shores that glisten under the Pacific’s pristine waters.

As a daily Mass-going Catholic devoted to Saint Damien of Molokai, she wanted to walk where he walked, pray where he prayed, and witness for herself the place — both stunning and haunting — where the late priest spent a pivotal part of his life caring for banished people sick with leprosy.

The pilgrimage to Kalaupapa, defined by its natural isolation in northern Molokai, is logistically challenging and restricted under normal circumstances. It is even more so today because of lingering COVID-19 pandemic restrictions that canceled all pilgrimages and tours of the national historical park to protect the peninsula’s eight remaining former patients. Park and state health department officials are considering when to resume organized pilgrimages and tours.

Hawaii Leprosy Colony Saints© Copyright 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

Hawaii Leprosy Colony Saints© Copyright 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reservedFor Toyofuku, a series of permissions came together at the right moment this summer. At the invitation of Kalaupapa’s priest, she retraced Father Damien’s footsteps in a place where for more than a century nearly no one wanted to go — and many would never leave.

Her husband, Lance Toyofuku, called all the difficulty God’s plan.

“Maybe the people who really want to get there will be able to go there,” he said. “You don’t want a million people going there every year.”

Kalaupapa, now a refuge for those who still call the peninsula home, was once the government’s answer to a deadly leprosy outbreak in the 1800s that persisted into the next century.

Missionaries, like Father Damien and Mother Marianne — who also became a Catholic saint following her service on the island — moved to Kalaupapa to care for the new residents’ physical and spiritual needs. The patients were immersed in suffering from the disease and the separation, said Alicia Damien Lau, one of two Catholic sisters currently living and serving on the peninsula, but the sick still found ways to thrive.

“The patients were all saints in a sense,” she said.

More than 8,000 people, mostly Native Hawaiians, perished at Kalaupapa, including Damien, who eventually contracted leprosy, later called Hansen’s disease. The Belgian priest, born Joseph De Veuster, is credited with drastically improving living conditions in the settlement.

“When you look at the surrounding areas, you could just feel the peace and spirit working in you,” said Lance Toyofuku, who lives in Hawaii’s capital city. “It’s not like being in Honolulu with all the cars and all the people.”

At the end of a gravel road, Damien’s grave site stands next to the church the priest expanded in 1876. The National Park Service, which cares for Kalaupapa’s cultural and historic resources, restored the church ahead of Damien’s 2009 canonization. His body was moved to Belgium in 1936. His right hand was reburied in 1995 at the site.

The group also prayed at the grave of Saint Marianne. Marianne Cope, who was born in Germany, died at Kalaupapa in 1918 of natural causes and was canonized in 2012.

Her dedication to caring for Kaluapapa’s people continues to provide comfort in the face of tragedy, like this summer’s devastating fire on the nearby island of Maui.

Soon after the blaze destroyed most of Sacred Hearts School, Principal Tonata Lolesio returned to the ashes of the Lahaina campus. She searched for a 12-inch metal statue of Marianne.

A quote from the nun served as a prominent message at the school: “Nothing is impossible. There are ways which lead to everything.”

Lolesio never found the Marianne statue, but the saint’s words help her lead the school as it continues to educate students at a temporary site.

Kalaupapa is the final resting place for so many, including Honolulu Bishop Larry Silva’s great-grandfather. Because of the disease’s stigma, Silva, like many others, didn’t learn of this piece of family history until he became an adult. When he joined pre-pandemic pilgrimages, he would point out his great-grandfather’s headstone along with Damien’s and Marianne’s graves during the settlement tours.

“The story of Kalaupapa is the story of isolation and fear,” said Silva, whose diocese includes the peninsula. But that’s not the full narrative, he said, “People were resilient and tried to make the best of it.”

A cure for Hansen’s disease was found in the mid-20th century. When the exile was lifted in 1969, some former patients chose to remain at Kalaupapa.

Kalaupapa’s quiet deepens at night, save for crashing ocean waves. The glow of axis deer eyes pierce the darkness as they dart between the settlement’s small houses — many of them vacant.

In the early mornings, Meli Watanuki’s truck is parked in front of St. Francis Church.

She chose to move to the settlement in 1969, after her husband abandoned her and took their son with him following her leprosy diagnosis. Now 88, she’s a regular at the 6 a.m. Mass along with the Catholic sisters and the occasional health department employee.

Watanuki explained that she didn’t learn about Damien and Marianne until moving to Kalaupapa.

“I love them so much,” she said through tears. “They keep me like this, make me strong.”

Bishop Silva and other church officials are eager for more people to make the pilgrimage once the diocese can resume the trips it hosted in partnership with tour companies owned by Kalaupapa residents – one of the few ways the public has been able to visit in the past.

“I have a whole list of people who said they’d like to go,” he said.

Keani Rawlins-Fernandez, the Molokai member of the Maui County Council, said many Molokai residents are nervous about tourism to Kalaupapa, which is sacred to Native Hawaiians like herself.

She worries what will become of the place when there are no more former patients living there.

On the peninsula, the walls of the house where Lau lives with Sister Barbara Jean Wajda are filled with photos of the sisters who worked on the settlement after Marianne. Lau and Wajda could be the last.

“Sister Alicia and I are committed to staying until the last patient leaves or dies,” Wajda said.

When there are no longer any patients, the state health department will also leave.

“And we both feel connected to the patients, to the land, to the saints who were here, declared and undeclared,” Wajda said. “And I think that the national park will be able to tell this story, but from a different perspective.”

Story by Jennifer Sinco Kelleher:Yhe Independent:

In the US, Black survivors are nearly invisible in the Catholic clergy sexual abuse crisis

In the US, Black survivors are nearly invisible in the Catholic clergy sexual abuse crisis

BALTIMORE (AP) — As Charles Richardson gradually lost his eyesight to complications from diabetes, certain childhood memories haunted him even more.

The Catholic priest appeared vividly in his mind’s eye — the one who promised him a spot on a travel basketball team, took him out for burgers and helped him with homework. The one, Richardson alleges, who sexually assaulted him for more than a year.

“I’ve been seeing him a lot lately,” Richardson said during a recent interview, dabbing tears from behind dark glasses.

As a Black middle schooler from northwest Baltimore, Richardson started spending time with the Rev. Henry Zerhusen, a charismatic white cleric. It was the 1970s and Zerhusen’s parish, St. Ambrose, was a fixture in Baltimore’s Park Heights neighborhood, which was then experiencing the effects of white flight and rapidly becoming majority-Black. Lauded as a “super-priest” when he died in 2003, Zerhusen welcomed his church’s racial integration and implemented robust social service programs for struggling families, including Richardson’s.

For most of his life, Richardson kept the abuse a secret, a common experience for survivors of sexual abuse. But cases of clergy abuse among African Americans are especially underreported, according to experts, who argue the lack of attention adds to the trauma of an already vulnerable population.

Black survivors like Richardson have been nearly invisible in the Catholic Church sexual abuse crisis — even in Baltimore, home to a historic Black Catholic community that plays an integral role in the nation’s oldest archdiocese. The U.S. Catholic Church generally does not publicly track the race or ethnicity of clergy abuse victims. Without that data, the full scope of clergy sex abuse and its effects on communities of color is unknown.

“Persons of color have suffered a long legacy of neglect and marginalization in the Catholic Church,” said the Rev. Bryan Massingale, a Black Catholic priest and Fordham University professor whose research has focused on the issue. “We need to correct the idea that all or most of the victims of this abuse have been white and male.”

Earlier this year, the Maryland Attorney General’s Office released a scathing report on child sex abuse within the Archdiocese of Baltimore dating back several decades. The report documents more than 600 abuse cases but leaves out any context about race. There are clues, however, in the names of priests and churches listed.

Out of 27 parishes in the archdiocese that have significant Black populations, at least 19 — 70% — previously had priests on staff who have been accused of sexual abuse, according to an Associated Press analysis. For parishes that experienced demographic shifts over time, these abusers were in residence in the years after Black membership increased and white membership declined.

Among those affected is St. Francis Xavier, one of the nation’s oldest Black Catholic churches, where four abusive priests have served over the decades. The parish’s first Black pastor, the late Rev. Carl Fisher, has been accused of abusing several children at St. Veronica’s, another majority-Black parish he served.

In 2013, decades after Richardson’s alleged abuse, Zerhusen faced accusations from another victim — the grandson of a woman who worked at St. Ambrose for 40 years. In response to that claim, two monsignors called Zerhusen “saintly” and unlikely to abuse, according to the attorney general’s report. The archdiocese ultimately settled with the victim for $32,500 and added Zerhusen to their list of credibly accused priests this past July.

Christian Kendzierski, a spokesperson for the archdiocese, said he was just learning of Richardson’s allegation about the late Zerhusen when contacted by the AP and didn’t have information on it.

Zerhusen worked with other abusive priests, including at St. Ambrose. At two more parishes, including after he was elevated to monsignor, he supervised four other priests later credibly accused of child sex abuse.

The last time Zerhusen abused him, Richardson said, he jumped out a stained-glass window to escape the church’s sanctuary, landing on the ground outside. In Richardson’s account, Zerhusen accompanied him to the hospital and told a doctor he landed on a Coke bottle playing football. Richardson still bears scars on his elbow that he attributes to the fall.

But the emotional scars have never healed. Until recently, he had never told his wife or adult daughters about the assaults.

Richardson dropped out of high school not long after the abuse. An aspiring professional tennis player, his game suffered, and he later became a car salesman. He still sometimes struggles when interacting with other men, especially in medical settings and situations involving physical contact.

As Black men, “we have a reputation we have to carry with us, a façade,” he said. “Something like this is one of the worst things — to say you have been raped or touched by another man.”

Not long after release of the attorney general’s report, Maryland lawmakers voted to repeal the statute of limitations for child sexual abuse victims to sue. At age 58, Richardson retained a lawyer and decided to go public.

Ray Kelly, a lifelong Catholic and chair of the pastoral council at St. Peter Claver, a Black parish in west Baltimore, said the archdiocese has repeatedly failed to address racial disparities, a trend that extends far beyond the clergy abuse crisis.

In response to the 2020 racial justice protests, Kelly helped lead a working group convened by the Baltimore archbishop that focused on combating racism, but he said the archdiocese took little action after receiving the group’s recommendations.

He pointed to the Catholic Church’s long history of treating African Americans like second-class citizens — beginning in Baltimore with the founding of the Oblate Sisters of Providence in 1829, when four Black women started their own religious order after being rejected by an existing sisterhood. One of the founders, Mother Mary Elizabeth Lange, is now being considered for sainthood.

The aftermath of the Civil War brought another new religious order to Baltimore: The Josephites were founded to minister to recently freed slaves. But despite their mission, for decades they largely did not admit Black men into the priesthood. The archdiocese now lists at least five Josephite priests as credibly accused of abuse.

“The Americanized Catholic Church still sees the Black population as a perpetual charity case, so to speak,” Kelly said. “And the predators are going to go where the prey is — Black communities relying on the church for support.”

Kendzierski, the archdiocese spokesperson, said its leaders have taken significant steps to address the church’s legacy of racism. He said the archdiocese’s Office of Black Catholic Ministry works to “lift up our Catholic social teaching related to the dignity of the human person and ensure worship is inclusive of the scope of the Catholic culture.”

In some cases, the church’s charity programs allowed abusers to reach African Americans who were not regulars at Mass. Richardson, for instance, was raised Baptist, but his family still relied on the local Catholic church for food, home repairs and other resources — a scenario that experts say is surprisingly common.

Abuse also came from within the Black community. Among the alleged perpetrators were some of the archdiocese’s few Black Catholic leaders.

When he was ordained in 1974, Maurice Blackwell was a celebrated rarity: a homegrown Black priest from west Baltimore. In the years since, he has been accused of sexually abusing at least 10 boys under 18, most at majority-Black parishes he pastored.

Darrell Carter alleges he was one of Blackwell’s victims. Now 63, he recently decided to sue under the new state law, which went into effect Oct. 1.

Carter’s father took him to Mass as a child. Before dying of cancer, he told Carter to find a Catholic church if he was ever in need: “They will help you.”

Money was scarce at home, and Carter often went hungry. As a teen, he visited St. Bernardine and later St. Edward — Black Catholic churches helmed by Blackwell — looking for odd jobs like shoveling snow to earn money. Instead, he said, Blackwell sexually abused him for four years and paid him $25 each time. Carter said Blackwell brandished a gun and threatened to kill him if he told anyone.

Carter said he reported the abuse to the archdiocese several years later, hoping to have Blackwell removed from ministry, but nothing came of it. The archdiocese said it received a report of Carter’s abuse in 2019 and reported it to law enforcement. Blackwell didn’t respond to recent messages seeking comment.

Carter went on to have a family and a welding career. He also struggled with alcoholism, suicidal thoughts and maintaining stable housing. Of the sexual abuse, he said, “There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t think about it.”

Carter’s attorney, Joanne Suder, who also represents Richardson and many other clergy abuse victims in Baltimore, said it’s common for people to wait decades before disclosing their abuse. She said that’s often the case even as they experience its debilitating impacts, including struggles with mental health and addiction.

In 2002, another of Blackwell’s victims — a young Black man named Dontee Stokes — showed up at the priest’s Baltimore rowhome, pulled out a handgun and shot Blackwell after he refused to apologize. The shooting became a defining event in Baltimore’s mishandling of clergy sex abuse claims, just as the scope of the crisis was breaking open in Boston.

Blackwell survived, and Stokes was later acquitted of attempted murder. He served 18 months of home detention for gun charges.

Stokes had reported the abuse nearly a decade before the shooting, but police never filed charges. Although the archdiocese found the claims credible, Cardinal William Keeler, then Baltimore’s archbishop, returned Blackwell to ministry against the advice of an independent review board. A psychiatrist who evaluated Blackwell noted the difficult situation, given his “leadership in the African American community as well as the intensely positive feelings of his parishioners.” Finally in 1998, Blackwell was removed from ministry after another victim came forward.

But it was only after the 2002 shooting that Blackwell was formally laicized and criminally charged. Despite being convicted of three counts of child sexual abuse, he was granted a new trial because of the “improper testimony about possible other victims,” according to the attorney general’s report. Prosecutors ultimately declined to retry him.

“Nobody got any closure,” said another of Blackwell’s victims, who received a settlement from the archdiocese.

The man spoke on the condition of anonymity, fearing being ostracized from his community if he publicly discussed his abuse. The AP generally does not identify sexual abuse victims without their consent. A runaway teen in the mid-1970s, the man ended up living in St. Bernardine’s rectory, where he said Blackwell sexually abused him. He came forward to support Stokes at trial.

For speaking out against Blackwell, the man got angry phone calls from friends and family members. “When you have somebody as popular as him, how can you knock the priest off his throne?” he said.

Blackwell remains popular, according to people in the community.

Gloria Webster also remembers feeling shunned by other Black Catholics.

“It was like I was suing God,” said Webster, who pursued criminal and civil charges on behalf of her daughter, who was sexually assaulted as a teenager. “All my friends turned against me.”

In 1990, Angelique Webster became suicidal, admitting she had been sexually abused for years by her white youth pastor, the Rev. Richard Deakin, starting when she was 13. The family lived down the block from the parish, St. Martin, where Gloria was an active volunteer.

Gloria and Angelique struggled to find other Black survivors: One support group for clergy abuse was filled with older white members. Gloria once called Blackwell for spiritual guidance but said she never heard back. Not long afterward, he was accused of abuse himself.

Then a graduate student in African American studies, Gloria was keenly aware of how gender and race played into the subsequent legal proceedings. She said the archdiocese tried to incorrectly “make it out like I’m this poor drug addict” who didn’t deserve support, but she was determined to fight for her daughter.

At the time, Maryland survivors generally had only a few years after the abuse to file a lawsuit, which meant Angelique navigated the case between multiple psychiatric hospitalizations. “I couldn’t hide from it because it was there all the time,” she said in a recent interview.

Deakin pleaded guilty to second-degree rape and child sex abuse, receiving no jailtime with a 20-year suspended sentence and five years’ probation. He had married by then and later became a licensed social worker at a Veterans Affairs facility in Pennsylvania. Because of his conviction, a state board ordered him to avoid counseling anyone under 21, according to licensing records. He surrendered his license in 2018 at the board’s request, which cited the public release of information about his sexual misconduct. He didn’t respond to a message seeking comment.

In 1993, the Websters settled out of court for $2.7 million, a staggering sum for the archdiocese, where most settlements fall under $100,000.

The settlement, paid in monthly installments, has allowed Angelique to afford ongoing therapy and maintain financial stability. Now married with a child of her own, she made a short documentary several years ago about Gloria’s fight as a Black woman to sue the Catholic Church.

Survivors coming forward now, including Richardson and Carter, will likely receive smaller settlements since the archdiocese recently declared bankruptcy, allowing it to protect its assets more and shift the litigation to bankruptcy court, a less transparent forum.

“I feel like they are escaping responsibility,” Richardson said.

But for his part, Richardson recently found solace in telling his daughter about the abuse: “A great weight has been lifted off my shoulders.”

He’s retired now, but Richardson recalled a moment that stood out during his long career as a car salesman — when another clergy abuse victim walked into his dealership. That was sometime after Stokes had shot Blackwell, and Richardson recognized him from widespread media coverage of the case. Before selling him a car, Richardson told Stokes he was proud of him for fighting back.

But he couldn’t yet say what he really wanted to share: that it happened to him too. Now, he finally can.

Pope Francis cancels Cop28 trip to Dubai due to ill health

Pope Francis cancels Cop28 trip to Dubai due to ill health

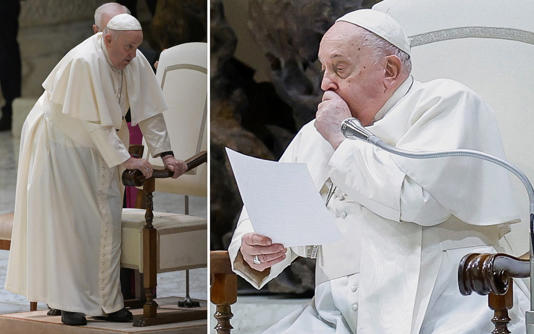

Pope Francis has cancelled a trip to the Cop28 climate summit in Dubai because of health issues.

The pontiff, who turns 87 on December 16, sounded wheezy and limited his speaking at a public event on Wednesday, a day after he cancelled the trip.

"Dear brothers and sisters good morning and welcome," he said at his weekly audience, held indoors in the Vatican's Paul IV hall.

He said an aide would read his main text in his place, "since I am still not well with this flu and (my) voice is not nice".

On Tuesday, the Vatican said Francis would no longer embark on his planned three-day trip to the United Nations' climate conference, known as Cop28, on doctors' recommendations.

The trip had been due to start on Friday and see him return to Rome on Sunday.

The Vatican said Francis, who had part of one lung removed as a young man, has flu and a lung inflammation that were causing him breathing problems.

"Although the Holy Father's general clinical condition has improved with regard to the flu and inflammation of the respiratory tract, doctors have asked the pope not to make the trip," a statement said.

The pontiff, who has made caring for the environment a priority of his papacy, wanted in some way to participate in the Cop28 discussions in the United Arab Emirates, according to the Holy See.

It was unclear if Francis might read his address to the climate conference by video link or take part in some other form.The Vatican said the pope had accepted the doctors' request "with great regret".

Francis, who has trouble walking due to a knee ailment and sometimes uses a wheelchair, arrived at his Wednesday audience walking, aided by a cane.

He was greeted in the packed audience hall by applause and chants of "Viva il papa" ("Long live the pope").

Francis was hospitalised earlier this year for three days for intravenous treatment with antibiotics of what the Vatican then said was bronchitis.

The Vatican said the pontiff in his current illness was receiving antibiotics intravenously.

In a televised appearance on Sunday, a cannula for intravenous use was visible on his right hand.

A CT scan, performed at a Rome hospital on November 25, had ruled out pneumonia, according to the Vatican.

A French bishop is accused of attempted rape in latest scandal to hit Catholic Church in France

A French bishop is accused of attempted rape in latest scandal to hit Catholic Church in France

A French bishop has been given a preliminary charge of attempting to rape an adult man a decade ago, the Paris prosecutor’s office said Monday. It is the latest of a growing number of accusations of sexual abuse by clergy in France.

The Bishops' Conference of France said the accused bishop, Georges Colomb, contests the charge and deserves the presumption of innocence. He has asked the Vatican to step aside from his duties as bishop of La Rochelle and Saintes in western France to prepare his defense.

French investigative website Mediapart reported that senior figures in the Catholic Church were aware of the accusations for years.

The allegations didn't reach prosecutors until May of this year. That's when lawyers for the Archdiocese of Paris and a Catholic group called the Foreign Missions of Paris, shortened to MEP in French, submitted a report of a rape attempt by Colomb in 2013, according to the prosecutor’s office.

Colomb headed the MEP from 2010 to 2016, and his accuser was staying in MEP facilities at the time of the incident, according to French media reports. Colomb became a bishop in 2016.

As a result of the ensuing investigation, Colomb was detained for questioning last week and magistrates filed a preliminary charge on Friday, the prosecutor’s office said. Colomb is under judicial supervision and barred from contact with the victim or witnesses pending further investigation.

His accuser has not been publicly named. After the alleged rape attempt, the man spoke about what happened to another official in the MEP, Gilles Reithinger.

Reithinger told public broadcaster France-3 that the man said Colomb proposed an oil massage that made him uncomfortable but didn’t mention any sexual wrongdoing. Reithinger, now bishop of Strasbourg, said he raised the issue with Colomb’s superior at the time but didn’t see any reason to report the incident to prosecutors.

The bishops' conference said in a statement Monday that it expresses its concern for the alleged victim, and offered support for ‘’all those who are troubled or hurt by this news.’’

A lawyer for Colomb did not respond to request for comment.

France is coming to terms with decades of covered-up abuse by church-related figures amid a global reckoning over the issue.

France’s bishops’ conference agreed to provide reparations after a 2021 report estimated some 330,000 children were sexually abused over 70 years by priests or other church-related figures in the country. The estimates were based on broader research by France’s National Institute of Health and Medical Research into sexual abuse of children.

Reference: The Independent:

Articles-Latest

- Koran burning conviction sparks fury as blasphemy law 'returns to UK'

- Robert Francis Prevost - Pope Leo XIV

- Pope Francis' death follows recent health challenges. Here's what we know about how he died.

- Easter April 2025 - international Celebrations

- The Rule of the twelve psalms -Worthy is the Lamb

- Religion in Africa Before Christianity and Islam

- 6 The Origin of Yahweh

- Dumo Di Milano

- What Did the Crow Tribe Believe In: Discover The Beliefs!

- 7 Reasons Historic Christianity Rejects the Book of Enoch

- 8 Breathtaking Mountain Monasteries Around the World

- Ethiopian Bible is oldest and most complete on earth

- Muhammad Muhammad was a prophet and founder of Islam.

- World Day of the Poor – SVP Christmas Campaign 2024

- Pope Francis to open 5 sacred portals on Christmas Eve — for a ritual that’s never been done before

- The 144,000 in Revelation

- Over 73 dead bodies 'used for meditation', 600 crocs in a pond, found in two Thai temples

- Occultism: Western Occult Tradition

- What is a Mudra

- Blood Sacrifices: Ancient Rituals of Life and Death

Articles-Most Read

- Home

- Let There Be Light

- Plants that feel and Speak

- The Singing Forest

- The Singing Forest-2

- Introduction

- Meditation

- Using Essential Oils for Spiritual Connection

- Heaven Scent

- Plants that Feel and Speak-2

- Purification

- Making the Spiritual Connection

- Anointing

- Essential Oils: The unseen Energies

- The Sanctity of Plants

- The Aroma Of Worship-Foreward

- The Aroma Of Worship - Introduction

- Methods Of Use

- Spiritual Blending

- Handling and Storage